How do I even begin to write about this book? I’ve been putting this post off because I really don’t know how to put my experience with Maus into words. It is, quite simply, one of the most powerful books I have ever read. But postponing this post won’t make writing it any easier, so here it goes.

How do I even begin to write about this book? I’ve been putting this post off because I really don’t know how to put my experience with Maus into words. It is, quite simply, one of the most powerful books I have ever read. But postponing this post won’t make writing it any easier, so here it goes.The events retold in Maus take place in Poland between the mid-30’s and 1945. They also take place in New York in the 1970’s and 1980’s. Maus is three things: the story of Art Spiegalman’s father’s, Vladek Spiegelman, survival; the story of a strenuous father and son relationship; and the story of the process of writing a comic book about the Holocaust.

The one thing everyone probably knows about Maus is that the Jews are portrayed as mice, the Nazis as cats, the Polish as pigs, the Americans as dogs, and so on. What you hear less often, though, is that, instead of turning the characters into caricatures, this portrayal increases their humanity, and thus the book’s poignancy. What shines through, past these animal faces, is the fact that people are the same – what we have in common is much greater than our differences, and there are both cruel and sympathetic people in every nationality, every ethnicity, every religion.

As I said before, Maus is as much about the Holocaust as it is about the enduring marks it left on the survivors and their families and about the process of trying to make sense of something this enormous through art. We are shown an adult Art Spiegelman asking his father to tell him the whole story – and this Vladek does. He tells him the story of the War and the pre- and post-War years, from meeting his future wife in the 1930s in Poland, to the increasing discrimination against Jewish people that first took their numerous family to a ghetto and later took the few surviving members to Auschwitz, from where only Vladek and his wife Anja escaped at the end of the war, seeking shelter in Sweden before moving to America.

Maus felt more personal than all the other holocaust stories I have encountered before, and I think the reason was the fact that the format of a father telling this story to a son allowed some complex and conflicting emotions to be expressed. What makes Maus so powerful is how raw, honest and human it is. It goes beyond a story in which the inhuman cruelties that Jewish people had to suffer are described (not that stories that “merely” describe those aren’t very much necessary). It shows what it is to have survived the unimaginable, and also what it is to have something that happened before you were born, something you are not sure you truly understand, be so acutely present in your life.

Art’s relationship with his father is, like I said, strenuous at best. The truth is that the present day Vladek is not a very likeable character. He is mean and demanding to those who surround him, he is obsessed with not spending a single unnecessary scent, and, most shocking of all, he is a racist. When his daughter-in-law asks him how he can be a racist after his whole life was shattered by anti-Semitism, he answers that you cannot even begin to compare a black man and a Jew.

All the questions that the reader struggles with throughout this book are the same questions Art Spiegelman is trying to find answers for. He realises that in many ways his father resembles the stereotype of the “miser old Jew”, and having to portray him as such worries him.

Many of these are, of course, unanswerable questions. To which extent did the overwhelming experience of the Holocaust turn his father into who he is today? What can be traced back to it, and what can’t? What can you expect from someone who went through something as overwhelming as that? What can you demand? And how much can you forgive and tolerate? How do you even begin to make sense of something like this?

Then there is the question of trying to portray this experience in the form of a comic book, and all the doubts, struggles and hesitations Art Spiegelman has to overcome. He considers giving up many times – fortunately for us, he didn’t, and he couldn’t have used a better approach to tell this story.

Art Spiegalman was born in Sweden after the War, and another question he has to struggle with is the extent to which he can understand the Holocaust even though he didn’t experience it himself. And yet its presence in his life is undeniable. His parents are haunted by the memories of those who didn’t survive, especially of their first-born son, Richeu. Richeu was poisoned by his aunt Tosha, who also poisoned herself, her daughter and another child at her guard when she was told that they were all going to be sent to Auschwitz, and there was nowhere else to hide. In 1968, his mother Anja commits suicide and doesn’t leave a note. Was it the experience of the death camps that caused it? Was it her lost son Richeu, her lost family? Was it Vladek? Was it something else? In an attempt to make sense of this, Art Spiegelman draws the mini-comic “Prisoner on Planet Hell”, which is reproduced in its integrity on Maus.

Another question raised in the book is if those who managed to survive, like his father, are to be admired, and if so, whether this means that not having survived is condemnable. And accepting that neither is the case is also accepting that something like the Holocaust is too horrible to have any sort of inner logic. There is no pattern that can be discerned. There is only utter senselessness and random death.

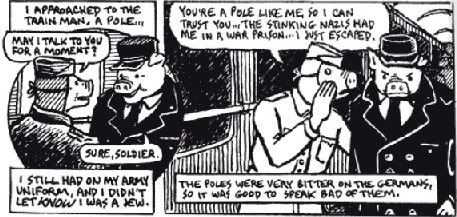

I know that this post is already very long, but I cannot finish without saying that Maus couldn’t be what it is if it wasn’t a comic. The art is an integral part of its power, of its poignancy. There’s the image that I posted above, of Vladek and Art in a classic storytelling pose, resembling a father and a young child, Vladek telling the story while his son takes notes. Then there are important details like the fact that when Vladek tries to pretend that he is not a Jew in Poland, he is shown wearing a pig mask:

And finally there is my favourite image:

This version of it that I found online is slightly different from the one in the book: there Vladek and Anja are shown from behind, walking aimlessly in the night towards the crossroad/swastika, and somehow they look even more vulnerable, even more forlorn, even more lost.

I urge you all to read Maus, even if – especially if – you are not a big fan of comics. I can’t think of a better book to demonstrate their power.

(Originally posted here)

2 comments:

Maus was the first graphic novel I ever read, and I guess I could literally say that it changed my life. Given the fact that it pushed me toward scholarly study in graphic narrative which has so drastically shaped the last 3 years of my life, I'd say that's pretty darn powerful.

Great review!

great history like The Italian Renaissance Graphic Novel AMBROGIO BECCARRIA is

quite engaging! Click here for a preview!

Thanx - a friend at illustrationISM

Post a Comment